I have never been so enveloped by religion as I have been in Ghana (and Uganda). I say this having spent time in Lhasa; Varanasi, India; Jerusalem; and Colorado Springs, Colorado. (Before you ask, no, I have not been to Vatican City yet. I can’t go to Mecca.) The pervasive presence of religion in Ghana really isn’t that surprising. A recent Gallup poll ranked Ghana as the number one most religious country with 96% self identifying as a religious person. (Iraq adds up to 88% religious and the US comes in at 60%.) It’s not surprising, but it is unfamiliar. Even at divinity school there was not such a deluge of religious language, symbols, and places of worship.

I have never been so enveloped by religion as I have been in Ghana (and Uganda). I say this having spent time in Lhasa; Varanasi, India; Jerusalem; and Colorado Springs, Colorado. (Before you ask, no, I have not been to Vatican City yet. I can’t go to Mecca.) The pervasive presence of religion in Ghana really isn’t that surprising. A recent Gallup poll ranked Ghana as the number one most religious country with 96% self identifying as a religious person. (Iraq adds up to 88% religious and the US comes in at 60%.) It’s not surprising, but it is unfamiliar. Even at divinity school there was not such a deluge of religious language, symbols, and places of worship.

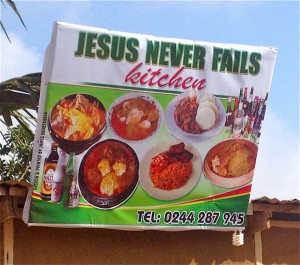

In Ghana I can hardly walk a block without seeing a church or mosque. Within a block of the office where I am working there are a dozen businesses with religious names that are unrelated to the service they provide—Jesus is Lord Mechanic, Christ Man Machine Repair, Blessed Salon. The only business I’ve seen in Ghana where the religious language has anything to do with the business is Let There Be Light Electricity.

In Ghana I can hardly walk a block without seeing a church or mosque. Within a block of the office where I am working there are a dozen businesses with religious names that are unrelated to the service they provide—Jesus is Lord Mechanic, Christ Man Machine Repair, Blessed Salon. The only business I’ve seen in Ghana where the religious language has anything to do with the business is Let There Be Light Electricity.

In addition to the numerous churches and business signs the vehicles on the road add to the religious cacophony with the religious slogans plastered on the windshields or bumpers. Many make sense—”Jesus is King,” “Allahu Akbar,” “God is Great,” “Am Blessed,” “Gye Nyame” (“except for God”). These seem to be simple affirmations of faith. Some, rather than give a slogan, only reference biblical or quranic verses or passages. Others are more cryptic—“Enemies are not God,” “1+1=3,” “Manchester United.” (That last one may be worship of a different kind.) One windshield asked me, “1+1=4 But Why?” I don’t know. Taxi, please tell me why. I do get one of the math ones—“1+1+1=1.” That’s definitely the math of the Trinity. One taxi merely states “Is God.” No punctuation or capitalization. I am at a loss. Is God what? God is? Is the taxi or taxi driving claiming to be God? Because I do believe that may be blasphemy.

In addition to the numerous churches and business signs the vehicles on the road add to the religious cacophony with the religious slogans plastered on the windshields or bumpers. Many make sense—”Jesus is King,” “Allahu Akbar,” “God is Great,” “Am Blessed,” “Gye Nyame” (“except for God”). These seem to be simple affirmations of faith. Some, rather than give a slogan, only reference biblical or quranic verses or passages. Others are more cryptic—“Enemies are not God,” “1+1=3,” “Manchester United.” (That last one may be worship of a different kind.) One windshield asked me, “1+1=4 But Why?” I don’t know. Taxi, please tell me why. I do get one of the math ones—“1+1+1=1.” That’s definitely the math of the Trinity. One taxi merely states “Is God.” No punctuation or capitalization. I am at a loss. Is God what? God is? Is the taxi or taxi driving claiming to be God? Because I do believe that may be blasphemy.

Many windshields give me direct commands. “Be Humble.” “Repent.” “Sin No More.” “Testify.” “Witness.” “Stop on Red.” Wait. I think that one was on a street sign.

Many windshields give me direct commands. “Be Humble.” “Repent.” “Sin No More.” “Testify.” “Witness.” “Stop on Red.” Wait. I think that one was on a street sign.

These kinds of commands are not unheard of in the US. I lived in Colorado Springs for four years. I’ve driven across Texas a dozen times. I’ve seen the billboards that command me to repent and remind me that the Kingdom is at hand. I’ve been behind vehicles with every rendition of the “Jesus fish” there is. There were bathtub altars in my neighbor’s yards growing up. There is no denying that in the US religion is everywhere. Yet, as a nonreligious person, I can go days, sometimes weeks, without hearing or seeing religious language. (But let’s be serious. I don’t go weeks. I love talking about religion.) In Ghana I can’t go outside with out being reminded of God. I guess that’s the point.

But as much as we argue about what separation of church and state means, as much as we, mostly nonChristians, complain about being bombarded by religion in the US, as much as we worry about when to say “Merry Christmas,” “Happy Holidays,” or just say “Good morning,” the US is a relatively easy place to be nonChristian and nonreligious. I’m not saying it’s perfect. I’m not saying the US is not a place where people are discriminated against, sometimes violently, for their nonChristianity. I’m not saying we need to stop working toward equality and true interbelief existence. I’m saying that living in a place where I am continually and constantly reminded on my religious otherness highlights how far the US has come toward that existence. It’s useful to have a reminder now and again.

But as much as we argue about what separation of church and state means, as much as we, mostly nonChristians, complain about being bombarded by religion in the US, as much as we worry about when to say “Merry Christmas,” “Happy Holidays,” or just say “Good morning,” the US is a relatively easy place to be nonChristian and nonreligious. I’m not saying it’s perfect. I’m not saying the US is not a place where people are discriminated against, sometimes violently, for their nonChristianity. I’m not saying we need to stop working toward equality and true interbelief existence. I’m saying that living in a place where I am continually and constantly reminded on my religious otherness highlights how far the US has come toward that existence. It’s useful to have a reminder now and again.

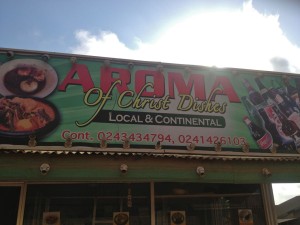

It’s also useful to remember that some of this religious language can be uplifting for even a nonreligious person like me. My favorite business name is the restaurant where we eat breakfast and dinner every day and lunch most days—Aroma of Christ Restaurant. How great is that? Everyone just calls it Aroma. I get the aroma connection to good food. But what exactly is the aroma of Christ? I never learned that at divinity school. Should that have been covered in New Testament or Christian theology?

A version of this post was published on State of Formation. Read it here.